Events

Students as Historians: Voting Rights History

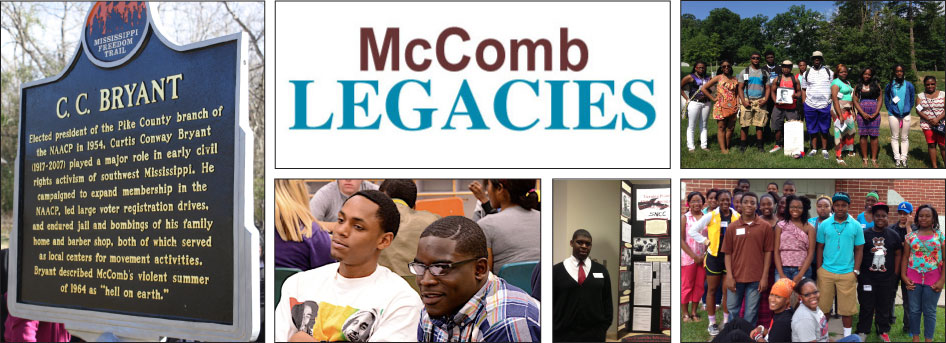

In July, twelve high school students from McComb stood in the hot shade of an Amite County farm and listened to a blues musician perform and tell stories about growing up in the area during the Civil Rights Movement. The students, ranging from ninth to twelfth grade and all from McComb, were on a field trip for a week-long summer institute studying voter registration efforts in their community. The musician, international performer Roosevelt Williams, Jr. (Juju Child), grew up next door to Herbert Lee, a black farmer and voting rights activist murdered in 1961, on whose land the students were standing.

In July, twelve high school students from McComb stood in the hot shade of an Amite County farm and listened to a blues musician perform and tell stories about growing up in the area during the Civil Rights Movement. The students, ranging from ninth to twelfth grade and all from McComb, were on a field trip for a week-long summer institute studying voter registration efforts in their community. The musician, international performer Roosevelt Williams, Jr. (Juju Child), grew up next door to Herbert Lee, a black farmer and voting rights activist murdered in 1961, on whose land the students were standing.

(Left to right) Brian Williams, Gabrielle Washington, and Zacchaeus McEwen conduct research.

The students spent the week uncovering the hidden past of the voter registration movement in Pike and Amite Counties. The murder of Herbert Lee and a witness, Louis Allen, were key pieces to the story. As one student wrote, “The main question on some of our minds was, ‘What really happened the day Herbert Lee was murdered’ and ‘How did the fight for the right to vote affect the people in the surrounding area?’”

In addition to Mr. Williams, students spoke with Lavelt Steptoe, Sr., the son of E.W. Steptoe, a black community leader who helped Mr. Lee organize local blacks to register to vote. “We have a class with your grandson,” the rising seniors informed Mr. Steptoe as he impressed upon them the importance of voting.

There is now a marker for Herbert Lee, thanks to Johnnie Powell, the owner of the Cotton Gin Restaurant.

They ate lunch with Mr. Steptoe at the Cotton Gin, the site where Mr. Lee was murdered by a white state representative who owned the land that bordered his.

The summer institute provided an opportunity for students to engage with history in a unique way by visiting local historic sites, role playing witness accounts, speaking with longtime residents, and analyzing primary documents including newspaper clips and oral history interviews.

From the research they gathered, the McComb students created drafts of a film documentary, stage performance, and a visual timeline. They will add new content to the student-run local history website McCombLegacies.org. During the fall students will continue to work on the film and performance as entries for the National History Day competition. The film about the Burglund Walkout produced in last year’s summer institute won a state level National History Day award.

The impact of the summer institute is best captured in students own words. “This institute has taught me that everyone has a chance to lead when they feel they need to,” reflected one student.

“I never knew all of this stuff happened in a place I don’t live too far from,” wrote a rising senior. “I’m actually learning more stuff now than I learn in class reading a textbook about world history. Local history is so much better because you actually can say, ‘Oh, I’ve been to that place,’ or ‘Oh, I’ve seen or spoken with that person.’ The more local history you know the more you have a chance to create a future for the next generation.”

When asked to compare the summer institute with most classes in school, they shared:

- In the classroom it’s the same history over and over again and you are only taught one side of the story. In this institute I learned about all sides of the story.

- [In school we learn] what the textbook wants us to know about history and it mainly focuses on what’s happening worldwide and is preached over and over. Whereas, the institute extends your learning and you’re able to learn about things locally as well as nationally hands on.

- The learning experience here was different from school in that we actually had to search and read the newspaper ourselves instead of somebody always giving us all the information. This institute had more hands-on and student-centered activities than some classes in school

They also reflected on how the institute challenged their perceptions of their community and civic engagement:

- I used to think that my community was boring and uninteresting, but after talking with the speakers, I have become very curious about what actually occurred.

- The more local history you know, the more you have a chance to create a future for the next generation.

- The most important thing that I learned this week was that I can change things and make history by what I do in life. I can also take things that are usually hidden and bring them back to life and be proud that I did it.

- After visiting the Cotton Gin, I feel more strongly about exercising my right to vote. I now know how important it is and I will definitely go register when I am of age.

- After doing countless interviews with local heroes of the movement, these videos will now be available for future generations to explore. When we go to National History Day we will show the world how important the Movement was in McComb.